Visualizing Prequel Meme Prefix Tries with Recursion Schemes

by Justin Le ♦

Source ♦ Markdown ♦ LaTeX ♦ Posted in Haskell, Tutorials ♦ Comments

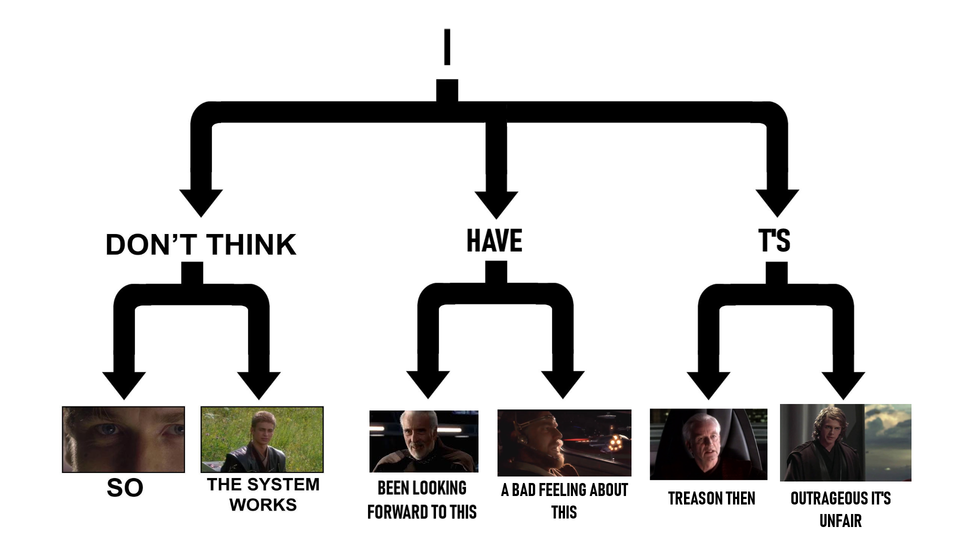

Not too long ago, I was browsing the prequel memes subreddit — a community built around creative ways of remixing and re-contextualizing quotes from the cinematic corpus of the three Star Wars “prequel” movies — when I noticed that a fad was in progress constructing tries based on quotes as keys indexing stills from the movie corresponding to those quotes.

This inspired me to try playing around with some tries myself, and it gave me an excuse to play around with recursion-schemes (one of my favorite Haskell libraries). If you haven’t heard about it yet, recursion-schemes (and the similar library data-fix) abstracts over common recursive functions written on recursive data types. It exploits the fact that a lot of recursive functions for different recursive data types all really follow the same pattern and gives us powerful tools for writing cleaner and safer code, and also for seeing our data types in a different light. The library is a pathway to many viewpoints — some considered to be particularly natural.

Recursion schemes is a perfect example of those amazing accidents that happen throughout the Haskell ecosystem: an extremely “theoretically beautiful” abstraction that also happens to be extremely useful for writing industrially rigorous code.

Is it possible to learn this power? Yes! As a fun intermediate-level Haskell project, let’s build a trie data type in Haskell based on recursion-schemes to see what it has to offer!

It’s Trie, Then

A trie (prefix tree) is a classic example of a simple yet powerful data type most people first encounter in college courses (I remember being introduced to it through a project implementing a boggle solver). The name comes from a pun on the word “re-trie-val”.

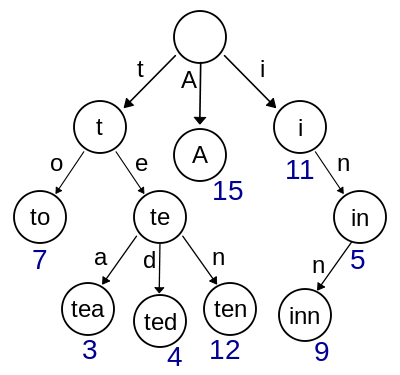

Wikipedia has a nice picture:

API-wise, it is very similar to an associative map, like the Map type from containers. It stores “keys” to “values”, and you can insert a value at a given key, lookup or check for a value stored at a given key, or delete the value at a given key. However, it is designed to be easy to (iteratively) find keys matching a given prefix. It’s also really fast to check if a given key is not in the trie, since it can return False as soon as a prefix is not found anywhere in the trie.

The main difference is in implementation: the keys are strings of tokens, and it is internally represented as a multi-level tree: if your keys are strings, then the first level branches on the first letter, the second level is the letter, etc. In the example above, the trie stores the keys to, tea, ted, ten, A, i, in, and inn to the values 7, 3, 4, 12, 15, 11, 5, and 9, respectively. As we see, it is possible for one key to completely overlap another (like in storing 5, and inn storing 9). We can also have partial overlaps (like tea, storing 3, and ted storing 4), whose common prefix (te) has no value stored under it.

Haskell Tries

We can represent this in Haskell by representing each layer as a Map of a token to the next layer of subtries.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L32-L33

data Trie k v = MkT (Maybe v) (Map k (Trie k v))

deriving ShowA Trie k v will have keys of type [k], where k is the key token type, and values of type v. Each layer might have a value (Maybe v), and branches out to each new layer.

We could write the trie storing (to, 9), (ton, 3), and (tax, 2) as:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L48-L61

testTrie :: Trie Char Int

testTrie = MkT Nothing $ M.fromList [

('t', MkT Nothing $ M.fromList [

('o', MkT (Just 9) $ M.fromList [

( 'n', MkT (Just 3) M.empty )

]

)

, ('a', MkT Nothing $ M.fromList [

( 'x', MkT (Just 2) M.empty )

]

)

]

)

]Note that this construction isn’t particularly sound, since it’s possible to represent invalid keys that have branches that lead to nothing. This becomes troublesome mostly when we implement delete, but we won’t be worrying about that for now. In Haskell, we have the choice to be as safe or unsafe as we want for a given situation. However, a “correct-by-construction” trie is in the next part of this series :)

Recursion Schemes: An Elegant Weapon

Now, Trie as written up there is an explicitly recursive data type. This might be common practice, but it’s not a particularly ideal situation. The problem with explicitly recursive data types is that to work with them, you often rely on explicitly recursive functions.

Within the functional programming community, explicitly recursive functions are notoriously difficult to write, understand, and maintain. It’s extremely easy to accidentally write an infinite loop, and explicit recursion is often called “the GOTO of functional programming”.

However, there’s a trick we can use to “factor out” the recursion in our data type. The trick is to replace the recursive occurrence of Trie k v (in the Map constructor) with a “placeholder” variable:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L32-L36

data Trie k v = MkT (Maybe v) (Map k (Trie k v))

deriving Show

data TrieF k v x = MkTF (Maybe v) (Map k x )

deriving (Functor, Show)TrieF represents, essentially, “one layer” of a Trie. It contains all of the structure of a single layer of a Trie: it contains all of the “guts” of what makes a trie a trie, except the recursion. It allows us to work with a single layer of a trie, encapsulating the essential structure. Later on, we’ll see that this means we sometimes don’t even need the original (recursive) Trie at all, if all we just care about is the structure.

For the rest of our journey, we’ll use TrieF as a non-recursive “view” into a single layer of a Trie. We can do this because recursion-schemes gives combinators (known as “recursion schemes”) to abstract over common explicit recursion patterns. The key to using recursion-schemes is recognizing which combinators abstracts over the type of recursion you’re using. It’s all about becoming familiar with the “zoo” of (colorfully named) recursion schemes you can pick from, and identifying which one does the job in your situation.

That’s the high-level view — let’s dive into writing out the API of our Trie!

Coarse boilerplate

One thing we need to do before we can start: we need to tell recursion-schemes to link TrieF with Trie. In the nomenclature of recursion-schemes, TrieF is known as the “base type”, and Trie is called “the fixed-point”.

Linking them requires some boilerplate, which is basically telling recursion-schemes how to convert back and forth between Trie and TrieF.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L38-L46

type instance Base (Trie k v) = TrieF k v

instance Recursive (Trie k v) where

project :: Trie k v -> TrieF k v (Trie k v)

project (MkT v xs) = MkTF v xs

instance Corecursive (Trie k v) where

embed :: TrieF k v (Trie k v) -> Trie k v

embed (MkTF v xs) = MkT v xsBasically, we are linking the constructors and fields of MkT and MkTF together.

Like the adolescent Anakin Skywalker, we usually don’t like boilerplate. It’s coarse and rough and irritating, and it gets everywhere. As with all boilerplate, it is sometimes useful to clean it up a bit using Template Haskell. The recursion-schemes library offers such a splice:

data Trie k v = MkT (Maybe v) (Map k (Trie k v))

deriving Show

makeBaseFunctor ''TrieThis will define TrieF with the MkTF constructor, and not just the Base type family, but the Recursive and Corecursive instances, too. It might even be more efficient than our hand-written way.

Humbly making our way across the universe

Time to explore the “zoo” of recursion schemes a bit! This is where the fun begins.

Whenever you get a new recursive type and base functor, a good first thing to try out is testing out cata and ana (catamorphisms and anamorphisms), the basic “folder” and “unfolder”.

I’ll try folding, that’s a good trick!

Catamorphisms are functions that “combine” or “fold” every layer of our recursive type into a single value. If we want to write a function of type Trie k v -> A, we can reach first for a catamorphism.

Catamorphisms work by folding layer-by-layer, from the bottom up. We can write one by defining “what to do with each layer”. This description comes in the form of an “algebra” in terms of the base functor:

myAlg :: TrieF k v A -> AIf we think of TrieF k v a as “one layer” of a Trie k v, then TrieF k v A -> A describes how to fold up one layer of our Trie k v into our final result value (here, of type A). Remember that a TrieF k v A contains a Maybe v and a Map k A. The A we are given (as the values of the given map) are the results of folding up all of the original subtries along each key; it’s the “results so far”. The values in the map become the very things we swore to create.

Then, we use cata to “fold” our value along the algebra:

cata myAlg :: Trie k v -> Acata starts from the bottom-most layer, runs myAlg on that, then goes up a layer, running myAlg on the results, then goes up another layer, running myAlg on those results, etc., until it reaches the top layer and runs myAlg again to produce the final result.

For example, we’ll write a catamorphism that counts how many values/leaves we have in our trie as an Int. Since our result is an Int, we know we want an algebra returning an Int:

countAlg :: TrieF k v Int -> IntThis is the basic structure of an algebra: our final result type (Int) becomes the parameter of TrieF k v (as TrieF k v Int), and also the result of our algebra.

Remember that a Trie k v contains a Maybe v and a Map k (Trie k v), and a TrieF k v Int contains a Maybe v and a Map k Int. In a Trie k v, the Map contains all of the subtries under each branch. For countAlg, in our TrieF k v Int we are given, the Map contains the counts of each of those original subtries under each branch.

Basically, our task is “Given a map of sub-counts, how do we find the total count?”

With this in mind, we can write countAlg:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L66-L71

countAlg :: TrieF k v Int -> Int

countAlg (MkTF v subtrieCounts)

| isJust v = 1 + subtrieTotal

| otherwise = subtrieTotal

where

subtrieTotal = sum subtrieCountsIf v is indeed a leaf (it’s Just), then it’s one plus the total counts of all of the subtries (remember, the Map k Int contains the counts of all of the original subtries, under each key). Otherwise, it’s just the total counts of all of the original subtries.

Our final count is, then:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L63-L64

count :: Trie k v -> Int

count = cata countAlgghci> count testTrie

3We can do something similar by writing a summer, as well, to sum up all values inside a trie:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L73-L77

trieSumAlg :: Num a => TrieF k a a -> a

trieSumAlg (MkTF v subtrieSums) = fromMaybe 0 v + sum subtrieSums

trieSum :: Num a => Trie k a -> a

trieSum = cata trieSumAlgghci> trieSum testTrie

14In the algebra, the subtrieSums :: Map k a contains the sums of all of the subtries. Under key k, we have the sum of the subtrie that was originally at kie k. The algebra, therefore, just adds up all of the subtrie sums with the value at that layer. “Given a map of sub-sums, how do we find a total sum?”

Down from the High Ground

Catamorphisms are naturally “inside-out”, or “bottom-up”. However, some operations are more naturally “outside-in”, or “top-down”. One immediate example is lookup :: [k] -> Trie k v -> Maybe v, which is quintessentially “top-down”: it first descends down the first item in the [k], then the second, then the third, etc. until you reach the end, and return the Maybe v at that layer.

Is that…legal?

In this case, we can make it legal by inverting control: instead of folding into a Maybe v directly, fold into a “looker upper”, a [k] -> Maybe v. We generate a “lookup function” from the bottom-up, and then run that all in the end on the key we want to look up.

Our algebra will therefore have type:

lookupperAlg

:: Ord k

=> TrieF k v ([k] -> Maybe v)

-> ([k] -> Maybe v)A TrieF k v ([k] -> Maybe v) contains a Maybe v and a Map k ([k] -> Maybe v), or a map of “lookuppers”. Indexed at each key is function of how to look up a given key in the original subtrie.

So, we are tasked with “how to implement a lookupper, given a map of sub-lookuppers”.

To do this, we can pattern match on the key we are looking up. If it’s [], then we just return the current leaf (if it exists). Otherwise, if it’s k:ks, we can run the lookupper of the subtrie at key k.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L87-L102

lookupperAlg

:: Ord k

=> TrieF k v ([k] -> Maybe v)

-> ([k] -> Maybe v)

lookupperAlg (MkTF v lookuppers) = \case

[] -> v

k:ks -> case M.lookup k lookuppers of

Nothing -> Nothing

Just lookupper -> lookupper ks

lookup

:: Ord k

=> [k]

-> Trie k v

-> Maybe v

lookup ks t = cata lookupperAlg t ks(written using the -XLambdaCase extension, allowing for \case syntax)

ghci> lookup "to" testTrie

Just 9

ghci> lookup "ton" testTrie

Just 3

ghci> lookup "tone" testTrie

NothingNote that because Maps have lazy values by default, we only ever actually generate “lookuppers” for subtries under keys that we eventually descend on; any other subtries will be ignored (and no lookuppers are ever generated for them).

In the end, this version has all of the same performance characteristics as the explicitly recursive one; we’re assembling a “lookupper” that stops as soon as it sees either a failed lookup (so it doesn’t cause any more evaluation later on), or stops when it reaches the end of its list.

I Think the System Works

We’ve now written a couple of non-recursive functions to “query” Trie. But what was the point, again? What do we gain over writing explicit versions to query Trie? Why couldn’t we just write:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L79-L81

trieSumExplicit :: Num a => Trie k a -> a

trieSumExplicit (MkT v subtries) =

fromMaybe 0 v + sum (fmap trieSumExplicit subtries)instead of

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L83-L85

trieSumCata :: Num a => Trie k a -> a

trieSumCata = cata $ \(MkTF v subtrieSums) ->

fromMaybe 0 v + sum subtrieSumsOne major reason, like I mentioned before, is to avoid using explicit recursion. It’s extremely easy when using explicit recursion to accidentally write an infinite loop, or to mess up your control flow somehow. It’s basically like using GOTO instead of while or for loops in imperative languages. while and for loops are meant to abstract over a common type of looping control flow, and provide a disciplined structure for them. They also are often much easier to read, because as soon as you see “while” or “for”, it gives you a hint at programmer intent in ways that an explicit GOTO might not.

Another major reason is to allow you to separate concerns. Writing trieSumExplicit forces you to think “how to fold this entire trie”. Writing trieSumAlg allows us to just focus on “how to fold this immediate layer”. You only need to ever focus on the immediate layer you are trying to sum — and never the entire trie. cata takes your “how to fold this immediate layer” function and turns it into a function that folds an entire trie, taking care of the recursive descent for you.

Aside

Before we move on, I just wanted to mention that cata is not a magic function. From the clues above, you might actually be able to implement it yourself. For our Trie, it’s:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L104-L105

cata' :: (TrieF k v a -> a) -> Trie k v -> a

cata' alg = alg . fmap (cata' alg) . projectFirst we project :: Trie k v -> TrieF k v (Trie k v), to “de-recursive” our type. Then we fmap our entire cata alg :: Trie k v -> a. Then we run the alg :: TrieF k v a -> a on the result. Basically, it’s fmap-collapse-then-collapse.

It might be interesting to note that the implementation of cata' here requires explicit recursion. One of the purposes of using recursion schemes like cata is to avoid directly using recursion explicitly, and “off-loading” the recursion to one reusable function. So in a sense, it’s ironic: cata can save other functions from explicit recursion, but not itself.

Or, can it? The reason cata' is necessarily recursive here is that our Trie data type is recursive. However, we can actually encode Trie using an alternative representation (in terms of TrieF), and it’s possible to write cata' in a non-recursive way:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L107-L110

newtype MuTrie k v = MkMT (forall a. (TrieF k v a -> a) -> a)

cataMuTrie :: (TrieF k v a -> a) -> MuTrie k v -> a

cataMuTrie alg (MkMT f) = f algTrie' is actually isomorphic to Trie, so they’re the same type (it’s actually type MuTrie k v = Mu (TrieF k v), using Mu from recursion-schemes). If you don’t believe me, here’s the isomorphism. This is actually one way we can encode recursive types in a language that doesn’t have any, like dhall.

Generating Tries

Anamorphisms, the dual of catamorphisms, will make another fine addition to our collection. They are functions that “generate” or “unfold” a value of a recursive type, layer-by-layer. If we want to write a function of type A -> Trie k v, we can reach first for an anamorphism.

Anamorphisms work by unfolding “layer-by-layer”, from the outside-in (top-down). We write one by defining “how to generate the next layer”. This description comes in the form of a “coalgebra” (pronounced like “co-algebra”, and not like coal energy “coal-gebra”), in terms of the base functor:

myCoalg :: A -> TrieF k v AIf we think of TrieF k v a as “one layer” of a Trie k v, then A -> TrieF k v A describes how to generate a new nested layer of our Trie k v from our initial “seed” (here, of type A). It tells us how to generate the next immediate layer. Remember that a TrieF k v A contains a Maybe v and a Map k A. The A (the values of the map) are then used to seed the new subtries. The As in the map are the “continue expanding with…” values.

We can then use ana to “unfold” our value along the coalgebra:

ana myCoalg :: A -> Trie k vana starts from an initial seed A, runs myCoalg on that, and then goes down a layer, running myCoalg on each value in the map to create new layers, etc., forever and ever. In practice, it usually stops when we return a TrieF with an empty map, since there are no more seeds to expand down. However, it’s nice to remember we don’t have to special-case this behavior: it arises naturally from the structure of maps.

While I don’t have a concrete “universal” example (like how we had count and sum for cata), the general idea is that if you want to create a value by repeatedly “expanding leaves”, an anamorphism is a perfect fit.

An example here that fits well with the nature of a trie is to produce a “singleton trie”: a trie that has only a single value at a single token string key.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L121-L125

mkSingletonCoalg :: v -> ([k] -> TrieF k v [k])

mkSingletonCoalg v = singletonCoalg

where

singletonCoalg [] = MkTF (Just v) M.empty

singletonCoalg (k:ks) = MkTF Nothing (M.singleton k ks)Given a v value, we’ll make a coalgebra [k] -> TrieF k v [k]. Our “seed” will be the [k] key (token string) we want to insert, and we’ll generate our singleton key by making sub-maps with sub-keys.

Our coalgebra (“layer generating function”) goes like this:

If our key-to-insert is empty

[], then we’re here! We’re at the layer where we want to insert the value at, soMkTF (Just v) M.empty. ReturningM.emptymeans that we don’t want to expand anymore, since there are no new seeds to expand into subtries.If our key-to-insert is not empty, then we’re not here! We return

MkTF Nothing…but we leave a singleton mapM.singleton k ks :: Map k [k]leaving a single seed. When we run our coalgebra withana,anawill go down and expand out that single seed (with our coalgebra) into an entire new sub-trie, withksas its seed.

So, we have singleton:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L118-L119

singleton :: [k] -> v -> Trie k v

singleton k v = ana (mkSingletonCoalg v) kWe run the coalgebra on our initial seed (the key), and ana will run singletonCoalg repeatedly, expanding out all of the seeds we deposit, forever and ever (or at least until there are no more values of the seed type left, which happens if we return an empty map).

ghci> singleton "hi" 7

MkT Nothing $ M.fromList [

('h', MkT Nothing $ M.fromList [

('i', MkT (Just 7) M.empty )

]

)

]A pathway to many subtries

Now that we’ve got the basics, let’s look at a more interesting anamorphism, where we leave multiple “seeds” along many different keys in the map, to generate many different subtries from our root. Twice the seeds, double the subtries.

Let’s write a function to generate a Trie k v from a Map [k] v: Given a map of keys (as token strings), generate a prefix trie containing every key-value pair in the map.

This might sound complicated, but let’s remember the philosophy and approach of writing an anamorphism: “How do I generate one layer”?

Our fromMapCoalg will take a Map [k] v and generate TrieF k v (Map [k] v): one single layer of our new Trie (in particular, the top layer). The values in each of the resultant maps will be later then watered and expanded into their own fully mature subtries.

So, how do we generate the top layer of a prefix trie from a map? Well, remember, to make a TrieF k v (Map [k] v), we need a Maybe v (the value at this layer) and a Map k (Map [k] v) (the map of seeds that will each expand into full subtries).

- If the map contains

[](the empty string), then there is a value at this layer. We will returnJust. - In the

Map k (Map [k] v), the value at keykis aMapcontaining all of the key-value pairs in the original map that start with k.

For a concrete example, if we start with M.fromList [("to", 9), ("ton", 3), ("tax", 2)], then we want fromMapCoalg to produce:

fromMap (M.fromList [("to", 9), ("ton", 3), ("tax", 2)])

= MkTF Nothing (

M.fromList [

('t', M.fromList [

("o" , 9)

, ("on", 3)

, ("ax", 2)

]

)

]

)The value is Nothing because we don’t have the empty string (so there is no to-level value), and the map at t contains all of the original key-value pairs that began with t.

Now that we have the concept, we can implement it using Data.Map combinators like M.lookup, M.toList, M.fromListWith, and M.union.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L127-L142

fromMapCoalg

:: Ord k

=> Map [k] v

-> TrieF k v (Map [k] v)

fromMapCoalg mp = MkTF (M.lookup [] mp)

(M.fromListWith M.union

[ (k , M.singleton ks v)

| (k:ks, v) <- M.toList mp

]

)

fromMap

:: Ord k

=> Map [k] v

-> Trie k v

fromMap = ana fromMapCoalgAnd just like that, we have a way to turn a Map [k] into a Trie k…all just from describing how to make the top-most layer. ana extrapolates the rest!

Again, we can ask what the point of this is: why couldn’t we just write it directly recursively? The answers are the same as before: first, to avoid potential bugs from explicit recursion. Second, to separate concerns: instead of thinking about how to generate an entire trie, we only need to be think about how to generate a single layer. ana reads our mind here, and extrapolates out the entire trie.

Aside

Again, let’s take some time to reassure ourselves that ana is not a magic function. You might have been able to guess how it’s implemented: it runs the coalgebra, and then fmaps re-expansion recursively.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L144-L145

ana' :: (a -> TrieF k v a) -> a -> Trie k v

ana' coalg = embed . fmap (ana' coalg) . coalgFirst, we run the coalg :: a -> TrieF k v a, then we fmap our entire ana coalg :: a -> Trie k v, then we embed :: TrieF k v (Trie k v) -> Trie k v back into our recursive type.

And again, because Trie is a recursive data type, ana is also necessarily one. However, like for cata, we can represent Trie in a way (in terms of TrieF) that allows us to write ana in a non-recursive way:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L147-L150

data NuTrie k v = forall a. MkNT (a -> TrieF k v a) a

anaNuTrie :: (a -> TrieF k v a) -> a -> NuTrie k v

anaNuTrie = MkNTNuTrie k v here is Nu (TrieF k v), from recursion-schemes. NuTrie is also isomorphic to Trie (as seen by this isomorphism), so they are the same type. We can also use it to represent recursive data types in a non-recursive language (like dhall).

I’ve been looking forward to this

So those are some examples to get our feet wet; now it’s time to build our prequel meme trie! Yipee!

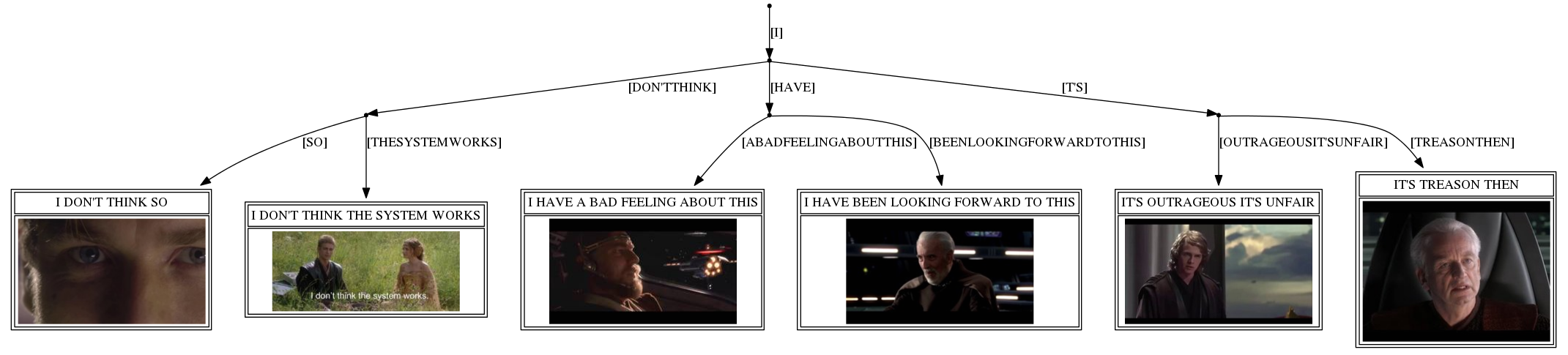

We’re going to try to re-create this reference trie: (full size here)

To render our tree, we’re going to be using the graphviz library, which generates a DOT file which the graphviz application can render. The graphviz library directly renders a value of the graph data type from fgl, the functional graph library that is the de-facto fleshed-out graph manipulation library of the Haskell ecosystem.

The roadmap seems straightforward:

- Load our prequel memes into a

Map String Label, a map of quotes to their associated macro images (as aLabel, which the graphviz library can render) - Use

anato turn aMap String Labelinto aTrie Char Label - Use

catato turn aTrie Char Labelinto aGr (Maybe Label) Chargraph of nodes linked by letters, with prequel meme leaves - Use the graphviz library to turn that graph into a DOT file, to be rendered by the external graphviz application.

1 and 4 are mainly fumbling around with IO, parsing, and interfacing with libraries, so 2 and 3 are the interesting steps in our case. We actually already wrote 2 (in the previous section — surprise!), so that just leaves 3 to investigate.

Monadic catamorphisms and fgl

fgl provides a two (interchangeable) graph types; for the sake of this article, we’re going to be using Gr from the Data.Graph.Inductive.PatriciaTree module1.

The type Gr a b represents a graph of vertices with labels of type a, and edges with labels of type b. In our case, for a Trie k v, we’ll have a graph with nodes of type Maybe v (the leaves, if they exist) and edges of type k (the token linking one node to the next).

Our end goal, then, is to write a function Trie k v -> Gr (Maybe v) k. Knowing this, we can jump directly into writing an algebra:

trieGraphAlg

:: TrieF k v (Gr (Maybe v) k)

-> Gr (Maybe v) kand then using cata trieGraphAlg :: Trie k v -> Gr (Maybe v) k.

This isn’t a particularly bad way to go about it, and you won’t have too many problems. However, this might be a good learning opportunity to practice writing “monadic” catamorphisms.

That’s because to create a graph using fgl, you need to manage Node ID’s, which are represented as Ints. To add a node, you need to generate a fresh Node ID. fgl has some nice tools for managing this, but we can have some fun by taking care of it ourselves using the so-called “state monad”, State Int.

We can use State Int as a way to generate “fresh” node ID’s on-demand, with the action fresh:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L158-L159

fresh :: State Int Int

fresh = state $ \i -> (i, i+1)fresh will return the current counter state to produce a new node ID, and then increment the counter so that the next invocation will return a new node ID.

In this light, we can frame our big picture as writing a Trie k v -> State Int (Gr (Maybe v) k): turn a Trie k v into a state action to generate a graph.

To write this, we lay out our algebra:

trieGraphAlg

:: TrieF k v (State Int (Gr (Maybe v) k))

-> State Int (Gr (Maybe v) k)We have to write a function “how to make a state action creating a graph, given a map of state actions creating sub-graphs”.

One interesting thing to note is that we have a lot to gain from using “first-class effects”: State Int (Gr (Maybe v) k) is just a normal, inert Haskell value that we can manipulate and sequence however we want. State is not only explicit, but the sequencing of actions (as first-class values) is also explicit.

We can write this using fgl combinators:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L166-L177

trieGraphAlg

:: TrieF k v (State Int (Gr (Maybe v) k))

-> State Int (Gr (Maybe v) k)

trieGraphAlg (MkTF v xs) = do

n <- fresh

subgraphs <- sequence xs

-- subbroots :: [(k, Int)]

let subroots = M.toList . fmap (fst . G.nodeRange) $ subgraphs

pure $ G.insEdges ((\(k,i) -> (n,i,k)) <$> subroots) -- insert root-to-subroots

. G.insNode (n, v) -- insert new root

. M.foldr (G.ufold (G.&)) G.empty -- merge all subgraphs

$ subgraphsFirst, generate and reserve a fresh node label

Then, sequence all of the state actions inside the map of sub-graph generators. Remember, a

TrieF k v (State Int (Gr (Maybe v) k))contains aMaybe vand aMap k (State Int (Gr (Maybe v) k)). The map contains State actions to create the sub-graphs, and we use:sequence :: Map k (State Int (Gr (Maybe v) k)) -> State Int (Map k (Gr (Maybe v) k))to turn a map of subgraph-producing actions into an action producing a map of subgraphs.

Note that this is made much simpler because of explicit state sequencing, since it gives us the opportunity to choose what “order” we want to perform our actions. Putting this after

freshensures that the nodes in the subtries all have larger ID’s than the root node. If we swap the order of the actions, we can actually invert the node ordering.Next, it’s useful to collect all of the subroots,

subroots :: [(k, Int)]. These are all of the node id’s of the roots of each of the subtries, paired with the token leading to that subtrie.Now to produce our result:

- First we merge all subgraphs (using

G.ufold (G.&)to merge together two graphs) - Then, we insert the new root, with our fresh node ID and the new

Maybe vlabel. - Then, we insert all of the edges connecting our new root to the root of all our subgraphs (in

subroots).

- First we merge all subgraphs (using

We can then write our graph generating function using this algebra, and then running the resulting State Int (Gr (Maybe v) k) action:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L161-L164

trieGraph

:: Trie k v

-> Gr (Maybe v) k

trieGraph = flip evalState 0 . cata trieGraphAlgFinally, we can write our mapToGraph:

mapToGraph

:: Ord k

=> Map [k] v

-> Gr (Maybe v) k

mapToGraph = flip evalState 0

. cata trieGraphAlg

. ana fromGraphCoalgHylomorphisms

Actually, writing things out as mapToGraph gives us some interesting insight: our function takes a Map [k] v, and returns a Gr (Maybe v) k. Notice that Trie k v isn’t anywhere in the type signature. This means that, to the external user, Trie’s role is completely internal.

In other words, Trie itself doesn’t seem to matter at all. We really want a Map [k] v -> Gr (Maybe v) k, and we’re just using Trie as an intermediate data structure. We are exploiting its internal structure to write our full function, and we don’t care about it outside of that. We build it up with ana and then immediately tear it down with cata, and it is completely invisible to the outside world.

One neat thing about recursion-schemes is that it lets us capture this “the actual fixed-point is only intermediate and is not directly consequential to the outside world” pattern. First, we walk ourselves through the following reasoning steps:

- We don’t care about

Trieitself as a result or input. We only care about it because we exploit its internal structure. TrieFalready expresses the internal structure ofTrie- Therefore, if we only want to take advantage of the structure, we really only ever need

TrieF. We can completely bypassTrie.

This should make sense in our case, because the only reason we use Trie is for its internal structure. But TrieF already captures the internal structure — thus, we really only need to ever worry about TrieF. We don’t actually care about the recursive data type — we never did!

In this spirit, recursion-schemes offers the hylomorphism recursion scheme:

hylo

:: (TrieF k v b -> b) -- ^ an algebra

-> (a -> TrieF k v a) -- ^ a coalgebra

-> a

-> bIf we see the coalgebra a -> TrieF k v a as a “building” function, and the algebra TrieF k v b -> b as a “consuming” function, then hylo will build, then immediately consume. It’ll build with the coalgebra on TrieF, then immediately consume with the algebra on TrieF. No Trie is ever generated, because it’s never necessary: we’re literally just building and immediately consuming TrieF values.

We could even implement hylo ourselves, to illustrate the “build and immediately consume” property:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L185-L192

hylo'

:: (TrieF k v b -> b) -- ^ an algebra

-> (a -> TrieF k v a) -- ^ a coalgebra

-> a

-> b

hylo' consume build = consume

. fmap (hylo' consume build)

. buildNote that the implementation of hylo given above works for any Functor instance: we build and consume along any Functor, taking advantage of the specific functor’s structure. The fixed-point never comes into the picture.

To me, being able to implement a function in terms of hylo (or any other refolder, like its cousin chrono, the chronomorphism) represents the ultimate “victory” in using recursion-schemes to refactor out your functions. That’s because it helps us realize that we never really cared about having a recursive data type in the first place. Trie was never the actual thing we wanted: we really just wanted its layer-by-layer structure. This whole time, we just cared about the structure of TrieF, not Trie. Being able to use hylo lets us see that the original recursive data type was nothing more than a distraction. Through it, we see the light.

I call the experiencing of making this revelation “achieving hylomorphism”.

Our final map-to-graph function can therefore be expressed as:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L179-L183

mapToGraph

:: Ord k

=> Map [k] v

-> Gr (Maybe v) k

mapToGraph = flip evalState 0 . hylo trieGraphAlg fromMapCoalgPack your things

To wrap things up, I made a text file storing all of the prequel quotes in the original reference trie along with images stored on my drive: (you can find a them online here)

I DON'T THINK SO,img/idts.jpg

I DON'T THINK THE SYSTEM WORKS,img/idttsw.jpg

I HAVE BEEN LOOKING FORWARD TO THIS,img/iblftt.jpg

I HAVE A BAD FEELING ABOUT THIS,img/ihabfat.jpg

IT'S TREASON THEN,img/itt.jpg

IT'S OUTRAGEOUS IT'S UNFAIR,img/tioiu.jpgWe can write a quick parser and aggregator into a Map [Char] HTML.Label, where HTML.Label is from the graphviz library, a renderable object to display on the final image.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L194-L203

memeMap :: String -> Map String HTML.Label

memeMap = M.fromList . map (uncurry processLine . span (/= ',')) . lines

where

processLine qt (drop 1->img) = (

filter (not . isSpace) qt

, HTML.Table (HTML.HTable Nothing [] [r1,r2])

)

where

r1 = HTML.Cells [HTML.LabelCell [] (HTML.Text [HTML.Str (T.pack qt)])]

r2 = HTML.Cells [HTML.ImgCell [] (HTML.Img [HTML.Src img])]We can also write a small utility function to clean up our final graph; it deletes nodes that only have one child and compacts them into the node above. It’s just to “compress” together strings of nodes that don’t have any forks.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L226-L236

compactify

:: Gr (Maybe v) k

-> Gr (Maybe v) [k]

compactify g0 = foldl' go (G.emap (:[]) g0) (G.labNodes g0)

where

go g (i, v) = case (G.inn g i, G.out g i) of

([(j, _, lj)], [(_, k, lk)])

| isNothing v -> G.insEdge (j, k, lj ++ lk)

. G.delNode i . G.delEdges [(j,i),(i,k)]

$ g

_ -> gWe could have directly outputted a compacted graph from trieGraphAlg, but for the sake of this post it’s a bit cleaner to separate out these concerns.

We’ll write a function to turn a Gr (Maybe HTML.Label) [Char] into a dot file, using graphviz to do most of the work:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L205-L215

graphDot

:: Gr (Maybe HTML.Label) String

-> T.Text

graphDot = GV.printIt . GV.graphToDot params

where

params = GV.nonClusteredParams

{ fmtNode = \(_, l) -> case l of

Nothing -> [GV.shape GV.PointShape]

Just l' -> [GV.toLabel l', GV.shape GV.PlainText]

, fmtEdge = \(_,_,l) -> [GV.toLabel (concat ["[", l, "]"])]

}And finally, we can write the entire pipeline:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/trie/trie.hs#L217-L224

memeDot

:: String

-> T.Text

memeDot = graphDot

. compactify

. flip evalState 0

. hylo trieGraphAlg fromMapCoalg

. memeMapShorter than I expected!

This gives us our final result: (full size here)

There are definitely some things we can tweak with respect to formatting and position and font sizes and label layouts, but I think this is fairly faithful to the original structure!

Another happy landing

There’s a lot more we can do with tries, and fleshing out a full interface allows us to explore a lot of other useful recursion schemes and combinators.

Now that we’ve familiarized ourselves with a simple tangible example, we’re now free to dive deep. Achieving hylomorphism helps us see past the recursive data type and directly into the underlying structure of what’s going on. And out of it, we got a pretty helpful meme trie we can show off to our friends.

In the next parts of the series, we’ll find out what other viewpoints recursion-schemes has to offer for us!

In the mean time, why not check out these other nice recursion-schemes tutorials?

- Bartosz Milewski also talks about using tries with recursion-schemes, and achieves hylomorphism as well.

- This classic tutorial was how I originally learned recursion schemes.

- This github repo accumulates a lot of amazing articles, tutorials, and other resources.

Special Thanks

I am very humbled to be supported by an amazing community, who make it possible for me to devote time to researching and writing these posts. Very special thanks to my supporters at the “Amazing” level on patreon, Sam Stites and Josh Vera! :)

Funny story, a patricia tree is actually itself a trie variation. This means that we are essentially converting a trie representing a graph into a graph representation implemented using a trie.↩︎