A (Dead End?) Arrowized Dataflow Parallelism Interface Attempt

by Justin Le ♦

Source ♦ Markdown ♦ LaTeX ♦ Posted in Haskell, Projects, Ramblings ♦ Comments

So I’ve been having several ‘dead end’ projects in Haskell recently that I’ve sort of just scrapped and move from, but I decided that it might be nice to document some of them :) For reading back on it later, for people to possibly help/offer suggestions, for people to peruse and possibly learn something, or for people to laugh at me. Here is my most recent semi-failure — implicit dataflow parallelism through an Arrow interface.

tl;dr:

- Compose parallelizable computations using expressive proc notation.

- Consolidate and join forks to maintain maximum parallelization.

- All data dependencies implicit; allows for nice succinct direct translations of normal functions.

- All “parallelizable” functions can also trivially be typechecked and run as normal functions, due to arrow polymorphism.

The main problem:

- Consider

ParArrow a c,ParArrow b d,ParArrow (c,d) (e,f),ParArrow e g, andParArrow f h. We execute the first two in parallel, apply the third, and execute the second two in parallel. Basically, we want two independentParArrow a gandParArrow c hthat we can fork. And this is possible, as long as the “middle” arrow does not “cross-talk” — that is, it can’t be something likearr (\(x,y) -> (y,x)).

The Vision

So what do I mean?

Dataflow Parallelism

By “dataflow parallelism”, I refer to structuring parallel computations by “what depends on what”. If two values can be computed in parallel, then that is taken advantage of. Consider something like map f xs. Normally, this would: one by one step over xs and apply f to each one, building a new list as you go along one at a time.

But note that there are some easy places to parallelize this — because none of the results the mapped list depend on each other, you can apply f to every element in parallel, and re-collect everything back at the end. And this is a big deal if f takes a long time. This is an example of something commonly referred to as “embarrassingly parallel”.

Arrows

So what kind of Arrow interface am I imagining with this?

Haskell has some nice syntax for composing “functions” (f, g, and h):

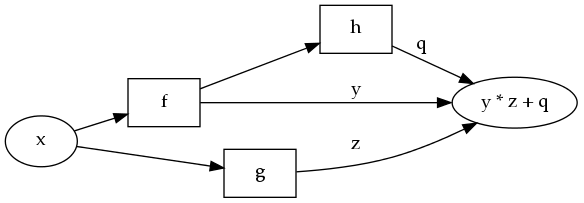

proc x -> do

y <- f -< x

z <- g -< x

q <- h -< y

returnA -< y * z + qA proc statement is a fancy lambda, which takes an input x and “funnels” x through several different “functions” — in our case, f, g, and h — and lets you name the results so that you can use them later.

While this looks like you are ‘performing’ f, then g, then h, what is actually happening is that you are composing and synthesizing a new function. You are “assembling” a new function that, when given an x, collects the results of x run through f, g, and h, and pops out a function of what comes out of those functions.

Except…f, g, and h don’t have to be normal functions. They are “generalized” functions; functions that could perhaps even have side-effects, or trigger special things, or be evaluated in special ways. They are instances of the Arrow typeclass.

An Arrow a b just represents, abstractly, a way to get some b from some a, equipped with combinators that allow you to compose them in neat ways. Proc notation allows us to assemble a giant new arrow, from sequencing and composing smaller arrows.

Forking Arrows

Look at the proc statement and tell me that that doesn’t scream “data parallelism” to you. Because every arrow f, g, and h can potentially do side-effecty, stateful, IO things, depending on how we implemented the arrow…what if f, g, and h represented “a way to get a b from an a…in its own separate thread”?

So if I were to “run” this special arrow, a ParArrow a b, I would do

runPar :: ParArrow a b -> a -> IO bWhere if i gave runPar a ParArrow a b, and an a, It would fork itself into its own thread and give you an IO b in response to your a.

Because of Arrow’s ability to “separate out” and “side-chain” compositions (note that q in the previous example does not depend on z at all, and can clearly be launched in parallel alongside the calculation of z), it looks like from a proc notation statement, we can easily write arrows that all ‘fork themselves’ under composition.

Using this, in the above proc example with the fancy diagram, we should be able to see that z is completely independent of y and q, so the g arrow could really compute itself “in parallel”, forked-off, from the f and h arrows.

You should also be able to “join together” parallel computations. That is, if you have an a -> c and a b -> d, you could make a “parallel” (a,b) -> (c,d). But what if I also had a c -> e and a d -> f? I could chain the entire a-c-e chain and the b-d-f chain, and perform both chains in parallel and re-collect things at the end. That is, a (a,b) -> (c,d) and a (c,d) -> (e,f) should meaningfully compose into a (a,b) -> (e,f), where the left and right sides (the a -> e and the b -> f) are performed “in parallel” from each other.

With that in mind, we could even do something like parMap:

parMap :: ParArrow a b -> ParArrow [a] [b]

parMap f = proc input -> do

case input of

[] ->

returnA -< []

(x:xs) -> do

y <- f -< x

ys <- parMap f -< xs

returnA -< y:ysAnd because “what depends on what” is so obviously clear from proc/do notation — you know exactly what depends on what, and the graph is already laid out there for you — and because f is actually a “smart” function, with “smart” semantics which can do things like fork threads to solve itself…this should be great way to structure programs and take advantage of implicit data parallelism.

The coolest thing

Also notice something cool – if leave our proc blocks polymorphic:

map' :: ArrowChoice r => r a b -> r [a] [b]

map' f = proc input -> do

case input of

[] ->

returnA -< []

(x:xs) -> do

y <- f -< x

ys <- map' f -< xs

returnA -< y:ysWe can now use map' as both a normal, sequential function and a parallel, forked computation!

λ: map' (arr (*2)) [1..5]

[2,4,6,8,10]

λ: runPar $ map' (arr (*2)) [1..5]

[2,4,6,8,10]Yup!

Let’s try implementing it, and let’s see where things go wrong.

ParArrow

Data and Instances

Let’s start out with our arrow data type:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/pararrow/ParArrow.hs#L12-L18

data ParArrow a b = Pure (a -> b)

| forall z. Seq (ParArrow a z)

(ParArrow z b)

| forall a1 a2 b1 b2. Par (a -> (a1, a2))

(ParArrow a1 b1)

(ParArrow a2 b2)

((b1, b2) -> b)So a ParArrow a b represents a (pure) paralleizable, forkable computation that returns a b (as IO b) when given an a.1

Pure fwraps a pure function in aParArrowthat computes that function in a fork when necessary.Seq f gsequences aParArrow a zand aParArrow z binto a bigParArrow a b. It represents composing two forkable functions into one big forkable function, sequentially.Par l f g rtakes twoParArrowsfandgof different types and represents the idea of performing them in parallel. Of forking them off from each other and computing them independently, and collecting it all together.landrare supposed to be functions that turn the tupled inputs/outputs of the parallel computations and makes them fitParArrow a b.ris kind of supposed to beid, andlis supposed to beid(to continue a parallel action) or\x -> (x,x)(to begin a fork).It’s a little hacky, and there might be a better way with GADT’s and all sorts of type/kind-level magic, but it was the way I found that I understood the most.

The main purpose of

landris to be able to meaningfully refer to the two parallelParArrows in terms of theaandbof the “combined”ParArrow. Otherwise, the two inputs of the two parallelParArrows don’t have anything to do with the input typeaof the combinedParArrow, and same for output.

Okay, let’s define a Category instance, that lets us compose ParArrows:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/pararrow/ParArrow.hs#L20-L22

instance Category ParArrow where

id = Pure id

f . g = Seq g fNo surprises there, hopefully! Now an Arrow instance:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/pararrow/ParArrow.hs#L24-L29

instance Arrow ParArrow where

arr = Pure

first f = f *** id

second g = id *** g

f &&& g = Par (id &&& id) f g id

f *** g = Par id f g idAlso simple enough. Note that first and second are defined in terms of (***), instead of the typical way of defining second, (&&&), and (***) in terms of arr and first.

The Magic

Now, for the magic — consolidating a big composition of fragmented ParArrows into a streamlined simple-as-possible graph:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/pararrow/ParArrow.hs#L31-L51

collapse :: ParArrow a b -> ParArrow a b

collapse (Seq f g) =

case (collapse f, collapse g) of

(Pure p1, Pure p2) -> Pure (p1 >>> p2)

(Seq s1 s2, _) -> Seq (collapse s1)

(collapse (Seq s2 g))

(_, Seq s1 s2) -> Seq (collapse (Seq f s1))

(collapse s2)

(Pure p, Par l p1 p2 r) -> Par (p >>> l)

(collapse p1) (collapse p2)

r

(Par l p1 p2 r, Pure p) -> Par l

(collapse p1) (collapse p2)

(r >>> p)

(Par l p1 p2 r,

Par l' p1' p2' r') -> let p1f x = fst . l' . r $ (x, undefined)

p2f x = snd . l' . r $ (undefined, x)

pp1 = collapse (p1 >>> arr p1f >>> p1')

pp2 = collapse (p2 >>> arr p2f >>> p2')

in Par l pp1 pp2 r'

collapse p = pThere are probably a couple of redundant calls to collapse in there, but the picture should still be evident:

Collapsing two sequenced

Pures should just be a singlePurewith their pure functions composed.Collapsing a

Seqsequenced with anything else should re-associate theSeqs to the left, and collapse theParArrows inside as well.Collapsing a

Pureand aParshould just involve moving the function inside thePureto the wrapping/unwrapping functions around thePar.Collapsing two

Pars is where the fun happens!We “fuse” the parallel branches of the fork together. We do that by running the export functions and the extract functions on each side, “ignoring” the other half of the tuple. This should work if the export/extract functions are all either

idorid &&& id.

And…here we have a highly condensed parallelism graph.

Inspecting ParArrow structures

It might be useful to get a peek at the internal structures of a collapsed ParArrow. I used a helper data type, Graph.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/pararrow/ParArrow.hs#L76-L79

data Graph = GPure -- Pure function

| Graph :->: Graph -- Sequenced arrows

| Graph :/: Graph -- Parallel arrows

deriving ShowAnd we can convert a given ParArrow into its internal graph:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/pararrow/ParArrow.hs#L81-L87

analyze' :: ParArrow a b -> Graph

analyze' (Pure _) = GPure

analyze' (Seq f g) = analyze' f :->: analyze' g

analyze' (Par _ f g _) = analyze' f :/: analyze' g

analyze :: ParArrow a b -> Graph

analyze = analyze' . collapseSample ParArrows

Let’s try examining it with some simple Arrows, like the one we mentioned before:

λ: let test1 =

| proc x -> do

| y <- arr (*2) -< x

| z <- arr (+3) -< x

| q <- arr (^2) -< y

| returnA -< y * z + q

λ: :t test1

test1 :: (Arrow r, Num t) => r t t

λ: test1 5

180

λ: analyze test1

GPure :/: GPureThis is what we would expect. From looking at the diagram above, we can see that there are two completely parallel forks; so in the collapsed arrow, there are indeed only two parallel forks of pure functions.

How about a much simpler one that we unroll ourselves:

λ: let test2 = arr (uncurry (+))

| . (arr (*2) *** arr (+3))

| . (id &&& id)

λ: :t test2

test2 :: (Arrow r, Num t) => r t t

λ: test2 5

18

λ: analyze' test2

((GPure :/: GPure) :->: (GPure :/: GPure)) :->: GPure

λ: analyze test2

GPure :/: GPureSo as we can see, the “uncollapsed” test2 is actually three sequenced functions (as we would expect): Two parallel pure arrows (the id &&& id and (arr (*2) *** arr (+3))) and then one sequential arrow (the arr (uncurry (+))).

However, we can see that that is just a single fork-and-recombine, so when we collapse it, we get GPure :/: GPure, as we would expect.

Running ParArrows

Now we just need a way to run a ParArrow, and do the proper forking. This actually isn’t too bad at all, because of what we did in collapse.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/pararrow/ParArrow.hs#L92-L113

runPar' :: ParArrow a b -> (a -> IO b)

runPar' = go

where

go :: ParArrow a b -> (a -> IO b)

go (Pure f) = \x -> putStrLn "P" >> return (f x)

go (Seq f g) = go f >=> go g

go (Par l f g r) = \x -> do

putStrLn "F"

fres <- newEmptyMVar

gres <- newEmptyMVar

let (fin,gin) = l x

forkIO $ runPar' f fin >>= putMVar fres

forkIO $ runPar' g gin >>= putMVar gres

reses <- (,) <$> takeMVar fres <*> takeMVar gres

return (r reses)

runPar :: ParArrow a b -> (a -> IO b)

runPar = runPar' . collapse(Note that I left in debug traces)

Testing

Sweet, now let’s run it!

λ: test2 5

18

λ: runPar test2 5

F

P

P

18That works as expected!

We can see from the debug trace that first things are forked, and then two pure functions are run. A final value of 18 is returned, which is the same as for the (->) version. (Note how we can use test2 as both, due to what we mentioned above)

Okay, so it looks like this does exactly what we want. It intelligently “knows” when to fork, when to unfork, when to “sequence” forks. Let’s try it with test1, which was written in proc notation.

λ: test1 5

180

λ: runPar test1 5

F

P

P

*** Exception: Prelude.undefinedWhat! :/

What went wrong

Let’s dig into actual desugaring. According to the proc notation specs:

test3 = proc x -> do

y <- arr (*2) -< x

z <- arr (+3) -< x

returnA -< y + z

-- desugared:

test3' = arr (\(x,y) -> x + y) -- add

. arr (\(x,y) -> (y,x)) -- flip

. first (arr (+3)) -- z

. arr (\(x,y) -> (y,x)) -- flip

. first (arr (*2)) -- y

. arr (\x -> (x,x)) -- splitAh. Everything is in terms of arr and first, and it never uses second, (***), or (&&&). (These should be equivalent, due to the Arrow laws, of course; my instance is obviously unlawful, oops)

I’m going to cut right to the chase here. The main problem is our collapsing sequenced Pure and Pars.

Basically, the collapsing rules say that if we have:

Par l p1 p2 r `Seq` Pure f `Seq` Par l' p1' p2' r'It should be the same as one giant Par, where f is “injected” between p1 and p1', p2 and p2'.

The bridge is basically a tuple, and we take advantage of laziness to basically pop the results of p1 into a tuple using r, apply f to the tuple, and extract it using l, and run it through p1'.

So f has to be some sort of function (a,b) -> (c,d), where c’s value can only depend on a’s value, and d’s value can only depend on b’s value. Basically, it has to be derived from functions a -> c and b -> d. A “parallel” function.

As long as this is true, this will work.

However, we see in the desugaring of test3 that f is not always that. f can be any function, actually, and we can’t really control what happens to it. In test3, we actually use f = \(x,y) -> (y,x)…definitely not a “parallel” function!

Actually, this doesn’t even make any sense in terms of our parallel computation model! How can we “combine” two parallel forks…when halfway in between the two forks, they must exchange information? Then it’s no longer fully parallel!

We can “fix” this. We can make collapse not collapse the Pure-Par cases:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/pararrow/ParArrow.hs#L53-L116

collapse_ :: ParArrow a b -> ParArrow a b

collapse_ (Seq f g) =

case (collapse_ f, collapse_ g) of

(Pure p1, Pure p2) -> Pure (p1 >>> p2)

(Seq s1 s2, _) -> Seq (collapse_ s1)

(collapse_ (Seq s2 g))

(_, Seq s1 s2) -> Seq (collapse_ (Seq f s1))

(collapse_ s2)

-- (Pure p, Par l p1 p2 r) -> Par (p >>> l)

-- (collapse_ p1) (collapse_ p2)

-- r

-- (Par l p1 p2 r, Pure p) -> Par l

-- (collapse_ p1) (collapse_ p2)

-- (r >>> p)

(Par l p1 p2 r,

Par l' p1' p2' r') -> let p1f x = fst . l' . r $ (x, undefined)

p2f x = snd . l' . r $ (undefined, x)

pp1 = collapse_ (p1 >>> arr p1f >>> p1')

pp2 = collapse_ (p2 >>> arr p2f >>> p2')

in Par l pp1 pp2 r'

(f,g) -> Seq f g

collapse_ p = p

analyze_ :: ParArrow a b -> Graph

analyze_ = analyze' . collapse_

runPar_ :: ParArrow a b -> (a -> IO b)

runPar_ = runPar' . collapse_Then we have:

λ: analyze_ test1

(

GPure :->: ( ( GPure :->: GPure ) :/: GPure )

) :->: ((

GPure :->: ( ( GPure :->: GPure ) :/: GPure )

) :->: ((

GPure :->: ( ( GPure :->: GPure ) :/: GPure )

) :->:

GPure

))We basically have three GPure :-> ((GPure :->: GPure) :/: GPure)’s in a row. A pure function followed by parallel functions. This sort of makes sense, and if we sort of imagined manually unrolling test3, this is what we’d imagine we’d get, sorta. now we don’t “collapse” the three parallel forks together.

This runs without error:

λ: runPar_ test1 5

P

F

P

P

P

P

F

P

P

P

P

18And the trace shows that it is “forking” two times. The structural analysis would actually suggest that we forked three times, but…I’m not totally sure what’s going on here heh. Still two is much more than what should ideally be required (one).

Oh.

So now we can no longer fully “collapse” the two parallel forks, and it involves forking twice. Which makes complete sense, because we have to swap in the middle.

And without the collapsing…there are a lot of unnecessary reforks/recominbations that would basically kill any useful parallelization unless you pre-compose all of your forks…which kind of defeats the purpose of the implicit dataflow parallelization in the first place.

Anyways, this is all rather annoying, because the analogous manual (&&&) / (***) / second-based test1 should not ever fail, because we never fork. So if the proc block had desugared to using those combinators and never using arr (\(x,y) -> (y,x)), everything would work out fine!

But hey, if you write out the arrow computation manually by composing (&&&), (***), and second…this will all actually work! I mean serious! Isn’t that crazy! (Provided, all of your Pure’s are sufficiently “parallel”).

But the whole point in the first place was to use proc/do notation, so this becomes a lot less useful than before.

Also, it’s inherently pretty fragile, as you can no longer rely on the type system to enforce “sufficiently parallel” Pure‘s. You can’t even check against something like arr (\(x,y) -> (x,x)), which makes no sense again in ’isolated parallel’ computations.

(Interestingly enough, you can use the type system to enforce against things like arr (\(x,y) -> x) or arr (\(x,y) -> 5); you can’t collapse tuples)

Basically, it mostly works for almost all ParArrow (a,b) (c,d)…except for when they have cross-talk.

So, well…back to the drawing board I guess.

What can be done?

So I’m open to seeing different avenues that this can be approached by, and also if anyone else has tried doing this and had more success than me.

In particular, I do not have much experience with type-/kind-level stuff involving those fun extensions, so if there is something that can be done there, I would be happy to learn :)

Other avenues

I have tried other things “in addition to” the things mentioned in this post, but most of them have also been dead ends. Among one of the attempts that I tried involve throwing exceptions from one thread to another containing the “missing half”. If an arr (\(x,y) -> (y,x))-like function is used, then each thread will know, and “wait” on the other to throw an exception to the other containing the missing data.

I couldn’t get this to work, exactly, because I couldn’t get it to work without adding a Typeable constraint to the parameters…and even when using things like the constrained monads technique, I couldn’t get the “unwrap” functions to work because I couldn’t show that z, a1, b1, etc. were Typeable.

Perhaps without the exception method, I could use MVars to sort of have a branch “wait” on the other if they find out that they have been given an arr that has cross-talk.

Another path is just giving up Arrow completely and using non-typeclass … but I don’t think that offers much advantages over the current system (using (***) etc.), and also it gives up the entire point — using proc notation, and also the neat ability to use them as if they were regular functions.

For now, though, I am calling this a “dead end”2; if anyone has any suggestions, I’d be happy to hear them :) I just thought it’d be worth putting up my thought process up in written form somewhere so that I could look back on them, or so that people can see what doesn’t work and/or possibly learn :) And of course for entertainment in case I am hilariously awful.

Technically, all

ParArrowcomputations are pure, so you might not loose too much by just returning abinstead of anIO bwithunsafePerformIO, but…↩︎Actually, this is technically not true; while I was writing this article another idea came to me by using some sort of state machine/automation arrow to wait on the results and pass them on, but that’s still in the first stages of being thought through :)↩︎