The List MonadPlus --- Practical Fun with Monads (Part 2 of 3)

by Justin Le ♦

Source ♦ Markdown ♦ LaTeX ♦ Posted in Haskell, Ramblings ♦ Comments

Part two of an exploration of a very useful design pattern in Haskell known as MonadPlus, a part of an effort to make “practical” monads less of a mystery and fun to the good peoples of this earth.

When we last left off on the MonadPlus introduction, we understood that there are times when you want to chain functions on objects in a way that “resembles” a failure/success process. We did this by exploring the most simple of all MonadPlus’s: a simple “dumb” container for a value is either in a success or a failure. We looked at how the MonadPlus design pattern really “behaved”.

This time we’re going to look at another MonadPlus — the List. By the end of this series we’re going to be using nothing but the list’s MonadPlus properties to solve this classic logic problem:

A farmer has a wolf, a goat, and a cabbage that he wishes to transport across a river. Unfortunately, his boat can carry only one thing at a time with him. He can’t leave the wolf alone with the goat, or the wolf will eat the goat. He can’t leave the goat alone with the cabbage, or the goat will eat the cabbage. How can he properly transport his belongings to the other side one at a time, without any disasters?

Let’s get to it!

MonadWhat? A review

Let’s take a quick review! Remember, a monad is just an object where you have defined a way to chain functions inside it. You’ll find that you can be creative this “chaining” behavior, and for any given type of object you can definitely define more than one way to “chain” functions on that type of object. One “design pattern” of chaining is MonadPlus, where we use this chaining to model success/failure.

mzeromeans “failure”, and chaining anything onto a failure will still be a failure.return xmeans “succeed withx”, and will return a “successful” result with a value ofx.

You can read through the previous article for examples of seeing these principles in action and in real code.

Without further ado, let us start on the list monad.

Starting on the List Monad

Now, when I say “list monad”, I mean “one way that you can implement chaining operations on a list”. To be more precise, I should say “haskell’s default choice of chaining method on lists”. Technically, there is no “the list monad”…there is “a way we can make the List data structure a monad”.

And what’s one way we can do this? You could probably take a wild guess. Yup, we can model lists as a MonadPlus — we can model chaining in a way that revolves around successes and failures.

So, how can a list model success/failure? Does that even make sense?

Let’s take a look at last article’s halve function:

-- the built in function `guard`, to refresh your memory

guard :: MonadPlus m => Bool -> m ()

guard True = return ()

guard False = mzero

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/monad-plus/Halves.hs#L30-L33

halve :: Int -> Maybe Int

halve n = do

guard $ even n

return $ n `div` 2ghci> halve 6

Just 3

ghci> halve 7

Nothing

ghci> halve 8 >>= halve

Just 2

ghci> halve 7 >>= halve

NothingHere, our success/fail mechanism was built into the Maybe container. Remember, first, it fails automatically if n is not even; then, it auto-succeeds with n `div` 2 (which only works if it has not already failed). But note that we didn’t actually really “need” Maybe here…we could have used anything that had an mzero (insta-fail, which is used in guard) and a return (auto-succeed).

Let’s see what happens when we replace our Maybe container with a list:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/monad-plus/Halves.hs#L35-L38

halve' :: Int -> [Int]

halve' n = do

guard $ even n

return $ n `div` 2This is…the exact same function body. We didn’t do anything but change the type signature. But because you believe me when I say that List is a MonadPlus…this should work, right? guard should work for any MonadPlus, because every MonadPlus has an mzero (fail). return should work for any MonadPlus, too — it wouldn’t be a MonadPlus without return implemented! (Remember, typeclasses are similar to interfaces in OOP) We don’t know exactly what failing and succeeding actually looks like in a list yet…but if you know it’s a MonadPlus (which List is, in the standard library), you know that it has these concepts defined somewhere.

So, how is list a meaningful MonadPlus? Simple: a “failure” is an empty list. A “success” is a non-empty list.

Watch:

ghci> halve' 6

[3]

ghci> halve' 7

[]

ghci> halve' 8 >>= halve'

[2]

ghci> halve' 7 >>= halve'

[]

ghci> halve' 32 >>= halve' >>= halve' >>= halve'

[2]

ghci> halve' 32 >> mzero >>= halve' >>= halve' >>= halve'

[]So there we have it! Nothing is just like [], Just x is just like [x]. This whole time! It’s all so clear now! Why does Maybe even exist, anyway, when we can just use [] and [x] for Nothing and Just x and be none the wiser? (Take some time to think about it if you want!)

In fact, if we generalize our type signature for halve, we can do some crazy things…

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/monad-plus/Halves.hs#L40-L43

genericHalve :: MonadPlus m => Int -> m Int

genericHalve n = do

guard $ even n

return $ n `div` 2ghci> genericHalve 8 :: Maybe Int

Just 4

ghci> genericHalve 8 :: [Int]

[4]

ghci> genericHalve 7 :: Maybe Int

Nothing

ghci> genericHalve 7 :: [Int]

[]Welcome to Haskell!

Now, when we say something like genericHalve 8 :: Maybe Int, it means “I want genericHalve 8…and I want the type to be Maybe Int.” This is necessary here because in our genericHalve can be any MonadPlus, so we have to tell ghci which MonadPlus we want.

(All three versions of halve available for playing around with)

So there you have it. Maybe and lists are one and the same. Lists do too represent the concept of failure and success. So…what’s the difference?

A List Apart

Lists can model failure the same way that Maybe can. But it should be apparent that lists can do a little “more” than Maybe…

Consider [3, 5]. Clearly this is to represent some sort of “success” (because a failure would be an empty list). But what kind of “success” could it represent?

How about we look at it this way: [3, 5] represents two separate paths to success. When we look at a Just 5, we see a computation that succeeded with a 5. When we see a [3, 5], we may interpret it as a computation that had two possible successful paths: one succeeding with a 3 and another with a 5.

You can also say that it represents a computation that could have chosen to succeed in a 3, or a 5. In this way, the list monad is often referred to as “the choice monad”.

This view of a list as a collection of possible successes or choices of successes is not the only way to think of a list as a monad…but it is the way that the Haskell community has adopted as arguably the most useful. (The other main way is to approach it completely differently, making list not even a MonadPlus and therefore not representing failure or success at all)

Think of it this way: A value goes through a long and arduous journey with many choices and possible paths and forks. At the end of it, you have the result of every path that could have lead to a success. Contrast this to the Maybe monad, where a value goes through this arduous journey, but never has any choice. There is only one path — successful, or otherwise. A Maybe is deterministic…a list provides a choice in paths.

halveOrDouble

Let’s take a simple example: halveOrDouble. It provides two successful paths if you are even: halving and doubling. It only provides one choice or possible path to success if you are odd: doubling. In this way it is slightly racist.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/monad-plus/HalveOrDouble.hs#L19-L21

halveOrDouble :: Int -> [Int]

halveOrDouble n | even n = [n `div` 2, n * 2]

| otherwise = [n * 2]ghci> halveOrDouble 6

[ 3,12]

ghci> halveOrDouble 7

[ 14](Play with this and other functions this section on your own)

As you can see in the first case, with the 6, there are two paths to success: the halve, and the double. In the second case, with the 7, there is only one — the double.

How about we subject a number to this halving-or-doubling journey twice? What do we expect?

- The path of halve-halve only works if the number is divisible by two twice. So this is only a successful path if the number is divisible by four.

- The path of halve-double only works if the number is even. So this is only a successful path in that case.

- The path of double-halve will work in all cases! It is a success always.

- The path of double-double will also work in all cases…it’ll never fail for our sojourning number!

So…halving-or-doubling twice has two possible successful paths for an odd number, three successful paths for a number divisible by two but not four, and four successful paths for a number divisible by four.

Let’s try it out:

ghci> halveOrDouble 5 >>= halveOrDouble

[ 5, 20]

ghci> halveOrDouble 6 >>= halveOrDouble

[ 6, 6, 24]

ghci> halveOrDouble 8 >>= halveOrDouble

[ 2, 8, 8, 32]The first list represents the results of all of the possible successful paths 5 could have taken to “traverse” the dreaded halveOrDouble landscape twice — double-halve, or double-double. The second, 6 could have emerged successful with halve-double, double-halve, or double-double. For 8, all paths are successful, incidentally. He better check his privilege.

Do notation

Let’s look at the same thing in do notation form to offer some possible insight:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/monad-plus/HalveOrDouble.hs#L24-L27

halveOrDoubleTwice :: Int -> [Int]

halveOrDoubleTwice n = do

x <- halveOrDouble n

halveOrDouble xDo notation describes a single path of a value. This is slightly confusing at first. But look at it — it has the exact same form as a Maybe monad do block.

This thing describes, in general terms, the path of a single value. x is not a list — it represents a single value, in the middle of its treacherous journey.

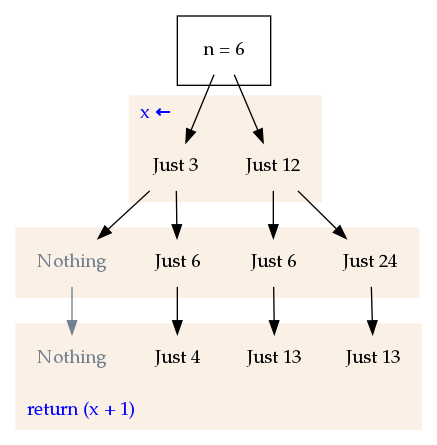

Here is an illustration, tracing out “individual paths”:

halveOrDoubleTwice :: Int -> [Int]

halveOrDoubleTwice n = do -- halveOrDoubleTwice 6

x <- halveOrDouble n -- x <- Just 3 Just 12

halveOrDouble x -- Nothing Just 6 Just 6 Just 24where you take the left path if you want to halve, and the right path if you want to double.

Remember, just like in the Maybe monad, the x represents the value “inside” the object — x represents a 3 or a 12 (but not “both”), depending on what path you are taking/are “in”. That’s why we can call halveOrDouble x: halveOrDouble only takes Ints and x is one Int along the path.

A winding journey

Note that once you bind a value to a variable (like x), then that is the value for x for the entire rest of the journey. In fact, let’s see it in action:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/monad-plus/HalveOrDouble.hs#L29-L29

hod2PlusOne :: Int -> [Int]

hod2PlusOne n = do -- hod2PlusOne 6

x <- halveOrDouble n -- x <- Just 3 Just 12

halveOrDouble x -- Nothing Just 6 Just 6 Just 24

return $ x + 1 -- (skip) Just 4 Just 13 Just 13ghci> hod2PlusOne 6

[ 4,13,13]Okay! This is getting interesting now. What’s going on? Well, there are four possible “paths”.

- In the half-half path,

x(the result of the first halving) is 3. However, the half-half path is a failure — 6 cannot be halved twice. Therefore, even thoughxis three, the path has already failed before we get to thereturn (x + 1). Just like in the case with Maybe, once something fails during the process of the journey, the entire journey is a failure. - In the half-double path,

xis also 3. However, this journey doesn’t fail. It survives to the end. After the doubling, the value of the journey at that point is “Just 6”. Afterwards, it “auto-succeeds” and replaces the current value with the value ofxon that path (3) plus 1 — 4. This is just like how in the Maybe monad, we return a new value after the guard. - In the double-halve path,

x(the result of the first operation, a double) is 12. The second operation makes the value in the journey a 6; At the end of it all, we succeed with whatever the value ofxis on that specific journey (12) is, plus one. 13. - Same story here, but for double-double;

xis 12. At the end of it all, the journey never fails, so it succeeds withx + 1, or 13.

Trying out every path

If this doesn’t satisfy you, here is an example of four Maybe do blocks where we “flesh out” each possible path, with the value of the block at each line in comments:

double :: Int -> Maybe Int

double n = Just n

halveHalvePlusOne :: Int -> Maybe Int

halveHalvePlusOne n = do -- n = 6

x <- halve n -- Just 3 (x = 3)

halve x -- Nothing

return $ x + 1 -- (skip)

halveDoublePlusOne :: Int -> Maybe Int

halveDoublePlusOne = do -- n = 6

x <- halve n -- Just 3 (x = 3)

double x -- Just 6

return $ x + 1 -- Just 4

doubleHalvePlusOne :: Int -> Maybe Int

doubleHalvePlusOne = do -- n = 6

x <- double n -- Just 12 (x = 12)

halve x -- Just 6

return $ x + 1 -- Just 13

doubleDoublePlusOne :: Int -> Maybe Int

doubleDoublePlusOne = do -- n = 6

x <- double n -- Just 12 (x = 12)

double x -- Just 6

return $ x + 1 -- Just 13A graphical look

This tree might also be a nice illustration, showing what happens at each stage of the journey.

Every complete “journey” is a complete path from top to bottom. You can see that the left-left journey (the half-halve journey) fails. The left-right journey (the halve-double journey) passes, and at the end is given the value of x + 1 for the x in that particular journey. The other journeys work the same way!

Solving real-ish problems

That wasn’t too bad, was it? We’re actually just about ready to start implementing our solution to the Wolf/Goat/Cabbage puzzle!

Before we end this post let’s build some more familiarity with the List monad and try out a very common practical example.

Finding the right combinations

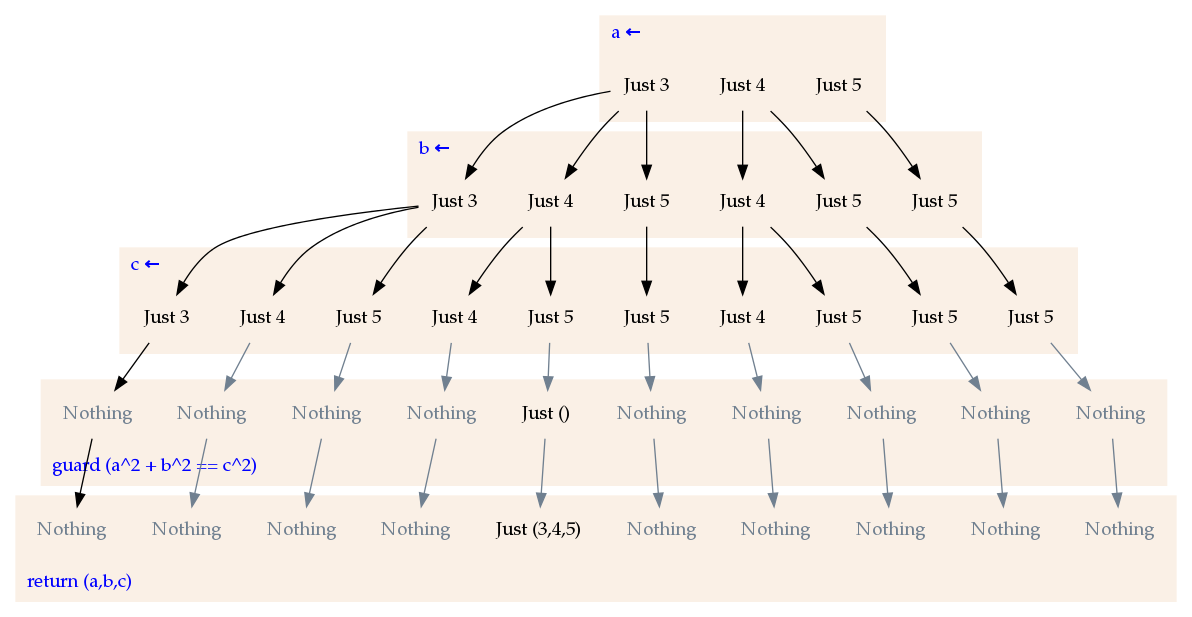

Here is probably the most common of all examples involving the list monad: finding Pythagorean triples.

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/monad-plus/TriplesUnder.hs#L12-L18

triplesUnder :: Int -> [Int]

triplesUnder n = do

a <- [1..n]

b <- [a..n]

c <- [b..n]

guard $ a^2 + b^2 == c^2

return (a,b,c)(Download it and try it out yourself!)

- Our journey begins with picking a number between 1 and

nand setting it toa. - Next, we pick a number between

aandnand set it tob. We start fromabecause if we don’t, we are probably going to be testing the same tuple twice. - Next, we pick a number between

bandn. This is our hypotenuse, and of course all hypontenii are larger than either side. - Now, we mercilessly and ruthlessly end all journeys who were unfortunate enough to pick a non-Pythagorean combination — combinations where

a^2 + b^2is notc^2 - For those successful journeys, we succeed with a tuple containing our victorious triple

(a,b,c).

Let’s try “following” this path with some arbitrary choices, looking at arbitrary journeys for n = 10:

- We pick

aas 2,bas 3, andcas 9. All is good until we get to the guard.a^2 + b^2is 10, which is notc^2(81), unfortunately. This(2,3,10)journey ends here. - We pick

aas 3,bas 4, andcas 5. On the guard, we succeed:a^2 + b^2is 25, which indeed isc^2. Our journey passes the guard, and then succeeds with a value of(3,4,5). This is indeed counted among the successful paths — among the victorious!

Paths like a = 5 and b = 3 do not even happen. This is because if we pick a = 5, then in that particular journey, b can only be chosen between 5 and n inclusive.

Remember, the final result is the accumulation of all such successful journeys. A little bit of combinatorics will show that there are \(\frac{1}{6} \times \frac{(n+2)!}{(n-1)!}\) possible journeys to attempt. Only the ones that do not fail (at the guard) will make it to the end. Remember how MonadPlus works — one failure along the journey means that the entire journey is a failure.

Let’s see what we get when we try it at the prompt:

ghci> triplesUnder 10

[ ( 3, 4, 5),( 6, 8,10) ]

ghci> triplesUnder 25

[ ( 3, 4, 5),( 5,12,13),( 6, 8,10),( 7,24,25)

,( 8,15,17),( 9,12,15),(12,16,20),(15,20,25) ]Perfect! You can probably quickly verify that all of these solutions are indeed Pythagorean triples. Out of the 220 journeys undertaken by triplesUnder 10, only two of them survived to the end to be successful. Out of the 2925 journeys in triplesUnder 25, only eight of them made it to the end. The rest “died”/failed, and as a result we do not even observe their remains. It is a cruel and unforgiving world.

While the full diagram of triplesUnder 5 has 35 branches, here is a diagram for those branches with \(a > 2\), which has 10:

Almost There!

Let’s do a quick review:

- You can really treat List exactly as if it were Maybe by using the general MonadPlus terms

mzeroandreturn. If you do this,Nothingis equivalent to[], andJust xis equivalent to[x]. Trippy! - However, whereas Maybe is a “deterministic” success, for a list, a list of successes represents the end results of possible paths to success. Chaining two “path splits” results in the item having to traverse both splits one after another.

- If any of these paths meet a failure at some point in their journey, the entire path is a failure and doesn’t show up in the list of successes. This is the “MonadPlus”ness of it all.

- When you use a do block (or reason about paths), it helps to think of each do block as representing one specific path in a Maybe monad, with arbitrary choices. Your

<-binds all represent one specific element, just like for Maybe.

The last point is particularly important and is pretty pivotal in understanding what is coming up next. Remember that all Maybe blocks and List blocks really essentially look exactly the same. This keeping-track-of-separate-paths thing is all handled behind-the scenes.

In fact you should be able to look at code like:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/monad-plus/TriplesUnder.hs#L12-L18

triplesUnder :: Int -> [Int]

triplesUnder n = do

a <- [1..n]

b <- [a..n]

c <- [b..n]

guard $ a^2 + b^2 == c^2

return (a,b,c)and see that it is structurally identical to

triplesUnder' :: Int -> Maybe Int

triplesUnder' n = do

a <- Just 3

b <- Just 5

c <- Just 8

guard $ a^2 + b^2 == c^2

return (a,b,c)for any arbitrary choice of a, b, and c, except instead of Just 3 (or [3]), you have [2,3,4], etc.

In fact recall that this block:

-- source: https://github.com/mstksg/inCode/tree/master/code-samples/monad-plus/Halves.hs#L40-L43

genericHalve :: MonadPlus m => Int -> m Int

genericHalve n = do

guard $ even n

return $ n `div` 2is general enough that it works for both.

Hopefully this all serves to show that in do blocks, Lists and Maybes are structurally identical. You reason with them the exact same way you do with Maybe’s. In something like x <- Just 5, x represents a single value, the 5. In something like x <- [1,2,3], x also represents a single value — the 1, the 2, or the 3, depending on which path you are currently on. Then later in the block, you can refer to x, and x refers to that one specific x for that path.

Until next time

So I feel like we are at all we need to know to really use the list monad to solve a large class of logic problems (because who needs Prolog, anyway?).

Between now and next time, think about how you would approach a logic problem like the Wolf/Goat/Cabbage problem with the concepts of MonadPlus? What would mzero/fail be useful for? What would the idea of a success be useful for, and what would the idea of “multiple paths to success” in a journey even mean? What is the journey?

Until next!